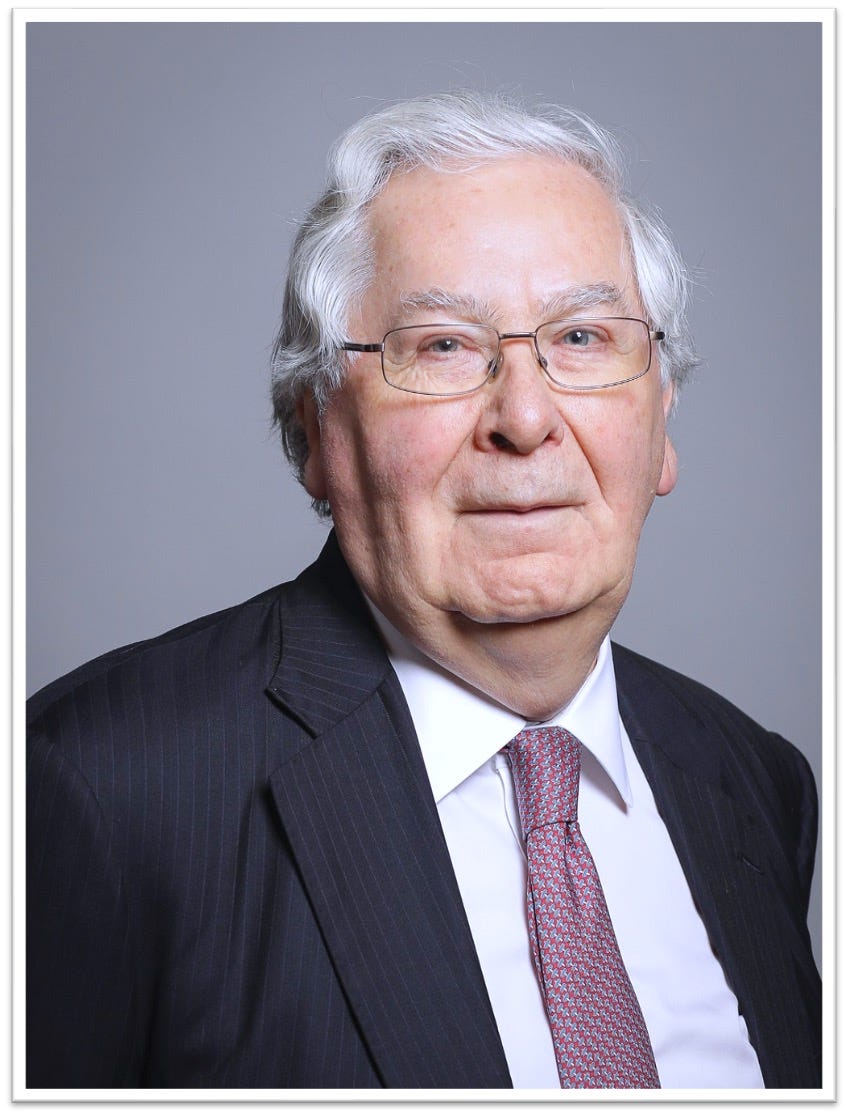

What to listen: Mervyn King on inflation

Inflation has struck back! Mervyn King, the former Governor of the Bank of England, was among the few economists (along with Larry Summers) who predicted this. In this conversation, he links his correct prediction with the old-school monetarist theory of inflation: lots of money chasing few goods.

Episode: “He Foresaw Inflation. Here’s What He Expects Next. Feat. Lord Mervyn King”.

Podcast: Capitalism isn’t

I have copied the extracts I found interesting below.

Bethany:….t was actually a year and a half ago that you came on our podcast, and you were almost alone in predicting inflation at the time. Larry Summers was saying there was going to be inflation, but the Federal Reserve and most central banks were saying inflation was not going to materialize. What did you see that everybody else seems to have missed?

Mervyn King: I think it’s not so much that they missed things as that they just were not looking and ignored it. Central banks were all seduced by a theory of inflation that said that inflation is driven entirely by expectations. If people believe inflation will stay low, then they will set prices and wages consistent with it staying low. But the question is, what drives expectations? What anchors expectations?

And in all the models that were created, the answer was, it’s the official inflation target. If central banks say they’re going to hit their inflation target, we’ll all believe it, and because we all believe it, that’s what will happen. Well, this is completely circular. I mean, when central banks say, “Inflation will stay low,” what they’re really saying is it will stay low because we say it will stay low, irrespective of what is going on in the economy.

It seemed to me pretty obvious that during 2020 and again in 2021, central banks decided to do a lot of quantitative easing. In other words, they printed money. And this was a very strange thing to do in those circumstances, because immediately prior to the COVID pandemic, there was a broad balance between demand and supply in the economy. What the pandemic did was to at least temporarily reduce potential supply. And the last thing you want to do in response to a reduction in potential supply is to boost demand, which is what printing money did.

This fancy theory of how inflation works should have been forgotten and replaced by the old, traditional approach, which was that inflation reflects too much money chasing too few goods. The pandemic gave us too few goods, and central banks gave us too much money. And the result, therefore, was pretty obvious. And I remember talking to Larry Summers about this, and what surprised us was that this was not a sophisticated error by central banks. It was a basic textbook error.

And it’s because all the economists working in central banks have been to the same graduate schools and studied the same very clever models. And they wanted to believe in these clever models, and they just forgot that if you got too much money chasing too few goods, you get inflation. And it really is as simple as that.

I think models can be very useful. But what they’re good at is helping you to think through something that’s very complicated, and you abstract from lots of things that are going on, and you’re trying to focus in the model on one key point of an argument and get your head around it. And then you throw the model away, and you take that insight into the world. Models give you insights, not forecasts. I think the big mistake was for central banks to think that the models that have been written down could be used for forecasting purposes. There were a number of people who did see this point and made the point, but central banks were attached to their models. I think what’s very interesting is to see how Jay Powell has now basically thrown all of that away, along with, I think, the idea of forward guidance. He must be pretty livid with his economists, I think.

Bethany: But help me understand this. How could an inflation target become a theory? I think, as you’ve said, that it seems redundant. It seems circular. It seems insane.

Mervyn King: It’s all those things. But if you go back before that, monetarism was the clear explanation of what drove inflation. And whether it was Milton Friedman really focusing on the monetary base or whether it was other people, there was this view that money lay behind inflation. And it didn’t prove to be a particularly successful forecaster during the 1980s, in particular, when there was a lot of financial innovation going on. So, people got disillusioned with this.

And I think, in combination with a wish to get away from the politics associated with Milton Friedman, people decided to construct a theory of inflation without money in the model at all. Now, at one level, this is sort of mad. It’s insane, as you said, Bethany, because inflation is a fall in the value of money. Well, how can you talk about the fall in the value of money without thinking about the demand and supply of money?

It’s quite difficult, and the trouble with it is that when you get down to simplifying the whole point of it, you need something to determine the nominal side of the model as opposed to the real side of the economy. And the only thing they had was the inflation target. But that is circular, as you said. The whole value of looking at money is not to pretend that it’s a mechanical guide to policy at all, but it’s a check.

And when people in the spring of 2021 should have noticed that the amount of broad money in the American economy was rising at 25 percent a year, the fastest rate since the end of the Second World War, the main question you should then ask is, “So, what’s going on?”

Bethany: You mentioned that you thought Jay Powell was quite angry at his economists and was thinking differently now going forward. Is he thinking differently? Is the Fed thinking differently? Are central banks thinking differently? Do you think economists will be trained differently, or is this adherence to models and belief in them so overwhelmingly appealing that nothing will change?

Mervyn King: Well, I fear that the adherence to models as the criterion that one uses to judge an economist or someone, whether they should get tenure in a university or have done well in their exams, it’s pretty much ingrained. And I think we need to find ways of relaxing it. But it isn’t so much the models as such as the way they’re misused. I don’t know what Jay Powell thinks now, but there’s a big shift in the tone of his speeches.

He’s abandoned forward guidance. He’s gone to meeting-by-meeting decisions. That’s what should always have been the sensible thing to do. And what I find most striking about his speeches is that the person he talks about most now is Paul Volcker. Now, of course, Paul Volcker was the most unpopular person in the US when he raised interest rates to 20 percent to combat inflation. But 20 years later on or 40 years later on, he is St. Paul.

And I think Jay Powell has a very good understanding that he doesn’t want to be known as the Arthur Burns of the Fed, who was the chair who thought about trying to bring inflation down but never did it to the extent that was needed. So, he left behind a legacy of high inflation. He wants to be the Paul Volcker, mark two, and to be known as St. Jay, or St. Jerome, rather, would be better, I think, in a few years’ time.