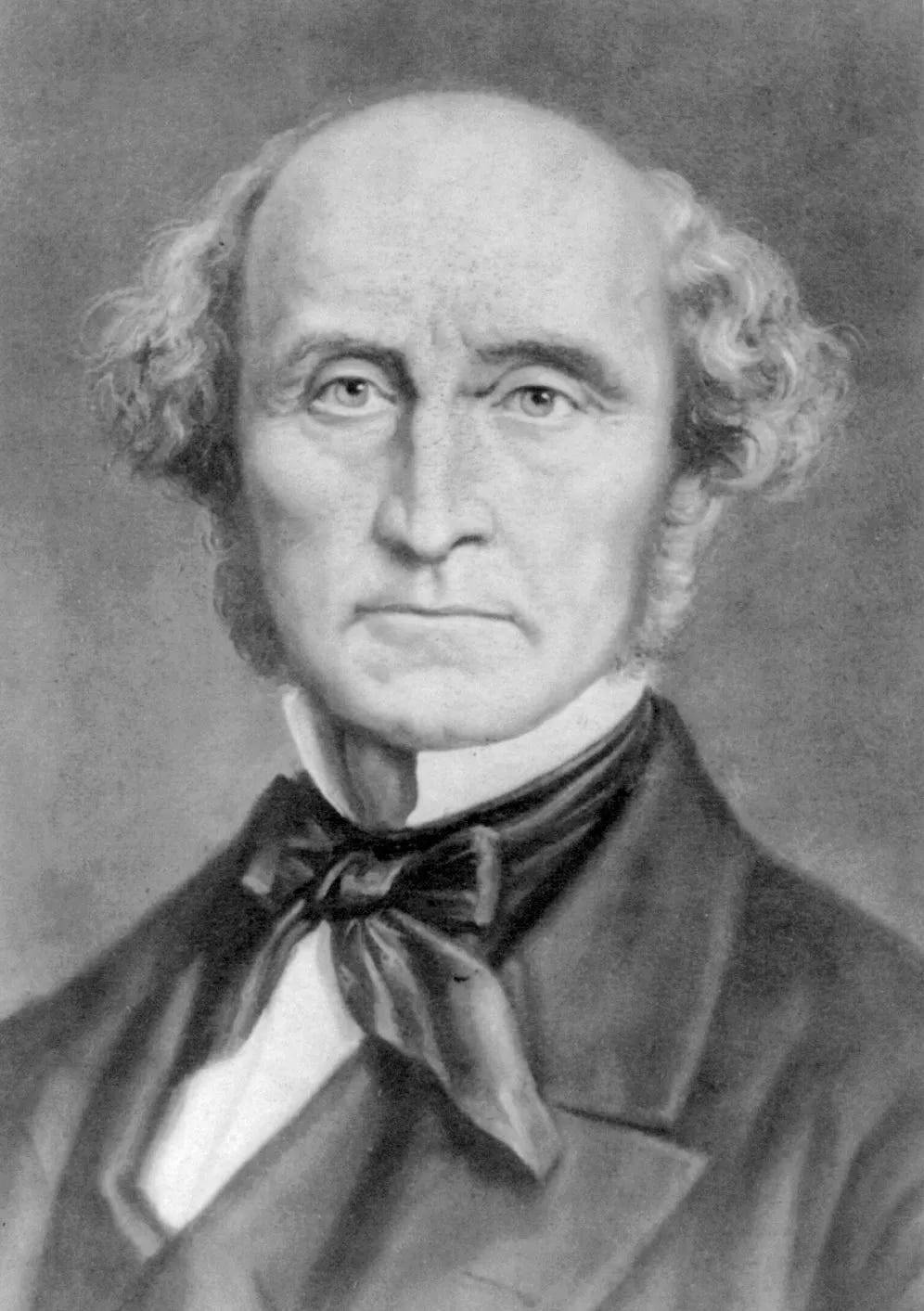

Book review: A very short introduction to John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill: A very short introduction

Author: Gregory Clays

Find the book in OUP and Amazon.

Before grabbing this book, I know very little about John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), apart from these basics:

A liberal philosopher, who presents a solid philosophical defence of individual freedom in his famous book “On liberty” (1859), using the “harms principle”: we ought to be free as long as we don’t harm others.

A classical liberal economist, who championed free market following Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

A feminist who promoted equal voting rights for women.

A Radical politician1, who played an active role in the expansion of democracy in Britain (the Second Reform Act 18672) and the emergence of progressive politics in the 19 century, especially the birth of the Liberal Party.

The book, however, was rather disappointing: no devoted chapter on his economic ideas while the rest of the chapters on his philosophy and political career were very scattered. Overall, I would give it 3 out of 10 and not recommended to the general reader. Nonetheless, I found the below extracts interesting.

Strong defence of free markets with little regard for the poor:

The Utilitarians zealously supported the new laissez-faire school of political economy, and broadly conceived corrupt and profligate aristocratic government and grossly unequal taxation as key causes of poverty. They believed the interests of the working and middle classes were largely identical, with wages resulting from a competitive bargain 'made in freedom' (in James Mill's terms) according to the law of supply and demand. They had little sympathy for the destitute sixth of the population; Bentham and James Mill commended a harsh regime of poor relief (welfare) to make any employment preferable to public handouts. Homo-ceconomicus was hard-working, diligent, thrifty, ingenious, and anxious to get ahead (p11).

His utilitarianism as a secular and instrumental defence of freedom:

Utilitarianism aims to show how promoting greater individuality is compatible with pursuing the greatest happiness for all. Its overarching goal is to defend a secular ethics against theologically based morality for a broadly traditionalist general public. Mill's starting point is that Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.

On his conception of liberty:

Mill defends what are today termed both 'negative' and 'positive' ideas of liberty; that is, we should be as free as possible from the coercion of others, but freedom should also be used for our self-development in specific directions, particularly towards virtue, self-mastery, and rationality, wherein the help of others may be vital. A negative liberty reading is frequently encountered among scholars, and even more the wider public. But Mill's bold introductory comment that the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it, is quite deceptive. Some see it as defending autonomy, or anarchic or libertarian self-rule. Carefully considered, however, this is a much less simple theory of liberty than we might initially assume. Mill's leading modern commentator, the philosopher Alan Ryan, insists that “Liberty” is not an essay about doing your own thing; it is an essay about finding the best thing and making it your own (p69)…[this suggests] that the libertarian or negative liberty reading of Mill is largely erroneous (p89).

As a Radical member of the parliament, his political aspiration was to limit the power of ruling families in Britain, which were represented by Tory party and Whig party:

The Benthamite Philosophic Radicals, whose moto for John Mill was enmity to the aristocratic principle, thus aimed more at destroying the political power of Britain's 200 or so ruling families than enfranchising the people as such. Extending voting potentially invited large numbers of the illiterate and ill-informed into the political process, with, following the trajectory of the French Revolution, the attendant possibility of disorder, and even the confiscation of the property of the rich. This threat agitated the younger Mill throughout his career. Parliamentary reform was both desirable and inevitable, as a corrupt oligarchy dominated by the aristocracy ruled Britain as what Bentham termed a “sinister interest” (p10).

The existing political landscape was dominated by two parties: the Tories, who usually favoured the landed interests, and the Whigs, who were more oriented towards commerce. Both remained wedded to a very restricted franchise, and to systematic bribery and corruption. The Tories in particular resisted free trade, especially in food; until 1846 substantial subsidies were paid to landlords in the form of the Corn Laws, which kept grain prices artificially high…The Radicals struggled to attain an identity independent of merely being the left wing of the Whig party. Creating this identity now became Mill's great goal (p25).

…In the unreformed Parliament, power was largely in the hands of the landed aristocracy and of government 'placemen? Seats were advertised for sale in newspapers, bribery of electors was common, and many newer industrial towns had no MPs at all. Westminster did not reflect the great shift in economic and social power wrought by the Industrial Revolution, or the ideas of popular sovereignty inherited from the French Revolution. After the first or “Great Reform Act of 1832”, the number of electors increased by some 60 per cent, and perhaps a hundred or more sympathizers of Benthamism entered the new Parliament (p26).

He clearly rejected Marx's revolutionary socialism. But:

By 1865, however, when running for Parliament, he conceded that he was deeply convinced that there can be no Parliamentary Reform worthy of the name, so long as a seat in Parliament is only attainable by rich men, or by those who have rich men at their back. As for Marx, only a distribution of economic power could alter this tendency (p65).

Wikipedia: “The Radicals were a loose parliamentary political grouping in Great Britain and Ireland in the early to mid-19th century who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party”.

UK Parliament: “The 1867 Reform Act (a) granted the vote to all householders in the boroughs as well as lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more And (b) reduced the property threshold in the counties and gave the vote to agricultural landowners and tenants with very small amounts of land”.